Museo Nazionale San Marco, Florence

Located on the wall of the East Corridor on the upper floor of the Dominican convent between cells 25 and 26 and painted in the mid 15th-century by Fra Angelico (1395-1455), the Madonna del Ombre – Madonna of the Shadows – is a particularly interesting work that showcases the exceptional talent of the beatified friar and the devotion of the donor and patron of the convent, Cosimo il Vecchio de’Medici (1389-1464).

Known today by a name that is linked to the perfect depiction in paint of the shadows that would be cast as the natural light of the corridor is absorbed by the capitals of the four pilasters in the work, in his time Beato Angelico’s masterpiece was known as a Sacra Conversazione.

A Sacred Conversation was a type of work popular in Renaissance art. Such paintings were populated by saints and angels surrounding an enthroned Madonna and Child who were engaged in some kind of dialogue with each other and – sometimes – the viewer. All were situated in a common or unified space giving potency and immediacy to the interaction.

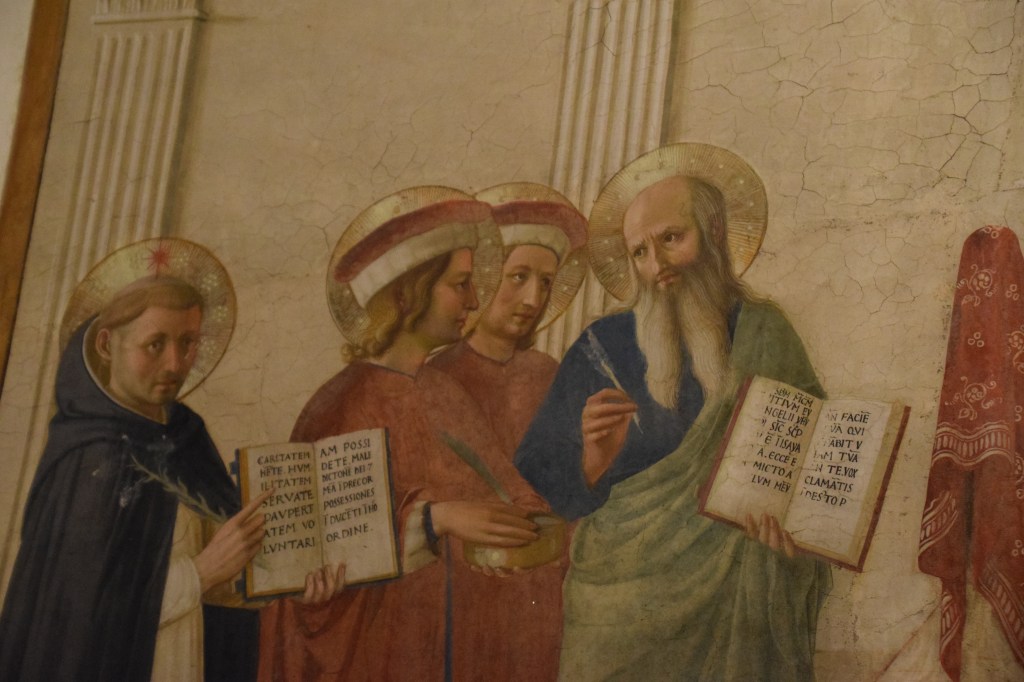

Fra Angelico’s fresco features eight saints – some dear to the Dominicans and some to Cosimo de’Medici – and an enthroned Madonna and Child. The saints, who are engaged in a silent interaction with each other, are organized in two symmetrically situated groups and they all occupy the same space with the enthroned Madonna and Child.

There are three holy persons who greet or ‘converse’ with the viewer’s eyes – one in each of the three groups that compose the fresco. With the exception of the Madonna whose eyes caress the young Jesus, Fra Angelico directs the gazes of all other saints to the order’s founder – San Domenico. To the viewer’s left the eyes of Domenico – founder of the order – greet us and direct our gaze to his invocation written in Latin on the open page of the book he holds.

In the central grouping, the young Jesus stares boldly forward presenting his authority with his blessing right hand and the Globus Cruciger in his left.

In the right symmetrical grouping of saints, San Lorenzo (225-258) serenely greets the eyes of the viewer. One of the six deacons of Rome, Lorenzo was executed by the orders of the Roman emperor Valerian (reign, 253-260). Although not the norm, Fra Angelico has identified Saint Lawrence as a protomartyr with his garb.

This Sacra Conversazione is the vernacular of religious and familial symbolism, declaring for the order, its’ gifted yet humble friar, and Cosimo il Vecchio de’Medici whose prosperity and piety made possible in paint this work. Below, the saints are featured individually and their place in the web that catches dwellers from both worlds explained.

Individually, to the viewers’ left are:

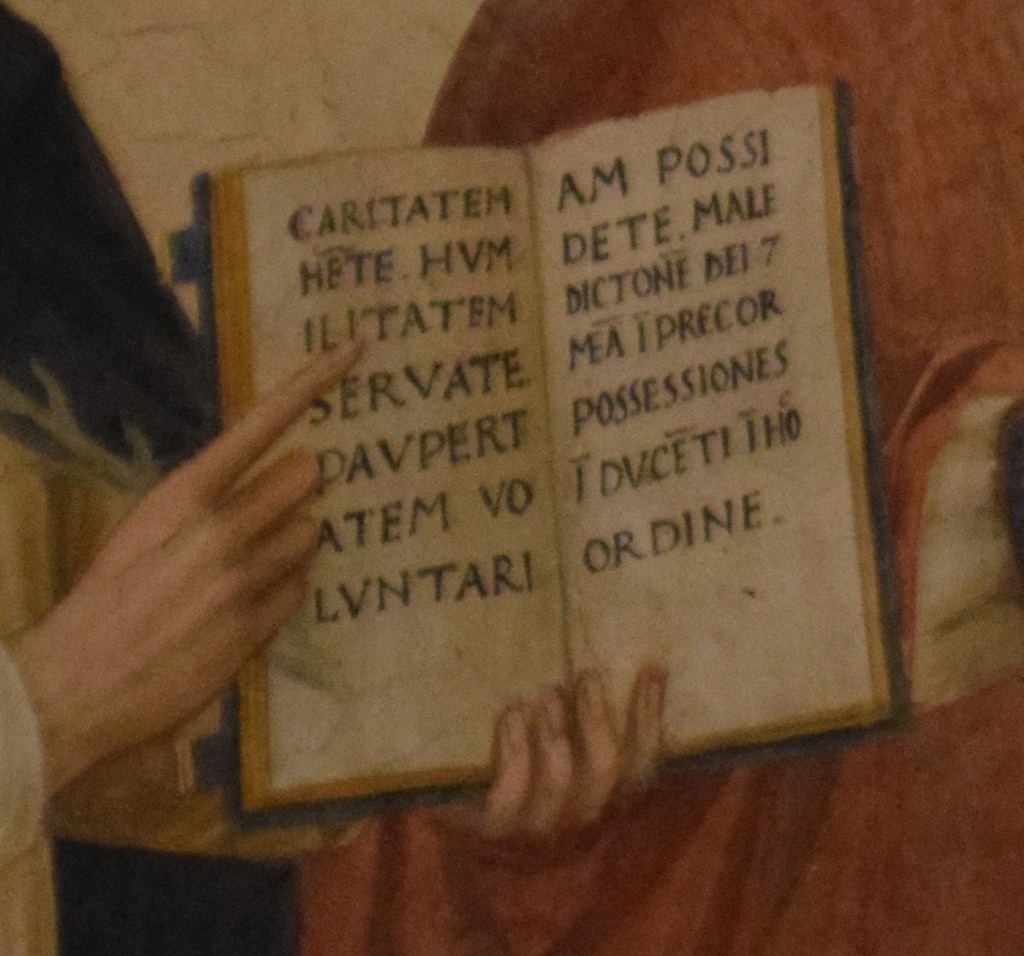

SAN DOMENICO DI GUZMAN (Spain, 1170 – Italy, 1221), founder of the Dominicans, is depicted with a red star on his head, a lily, and a book. The legible Latin words are associated with the Dominican friars and speak to a fundamental motto of the order and an invocation of its’ founder. Those words are:

Latin: “Caritatem habete, humilitatem servate, paupertatem voluntariam possidete. Maledictionem Dei et meam imprecor possessiones inducentibus in hoc ordine”

English: “Have charity, observe humility, possess voluntary poverty. I implore the curse of God and mine on those who introduce possessions in this order.”

The red star above Domenico’s forehead symbolizes the holy vision experienced by his godmother who saw a star on his forehead during his Baptism. The star embodies the light and illumination that Saint Dominic brought to the world. The lily symbolizes his chastity and purity. The book itself represents the gospels by which he lived. Because of the easy association of the star with the heavens, San Domenico is the patron saint of astronomers. The gaze of San Domenico falls on the viewer in order to catch our eyes and to direct them to the words that school both us and his brother friars.

Immediately to San Domenico’s left are the twins SAN COSMA and SAN DAMIANO (died 287 or 303 A.D.), the Arab mendicant physicians and martyrs who died together in the early 4th century A.D during the purge of Christians ordered by the Roman emperor Diocletian (284-305 A.D.). The brothers are patron saints of the Medici family – the family of the donor Cosimo de’Medici – and Cosmo is the name-saint of Cosimo making him dear to the donor in a personal and dedicatory sense. In the hands of the brother in the foreground is a ‘box’ which carries the tools of their trade. The saints have identical faces and wear matching hats which signify their fraternal affiliation. The eyes of both Cosma and Damiano are fixed on the saint to their left – Saint Mark.

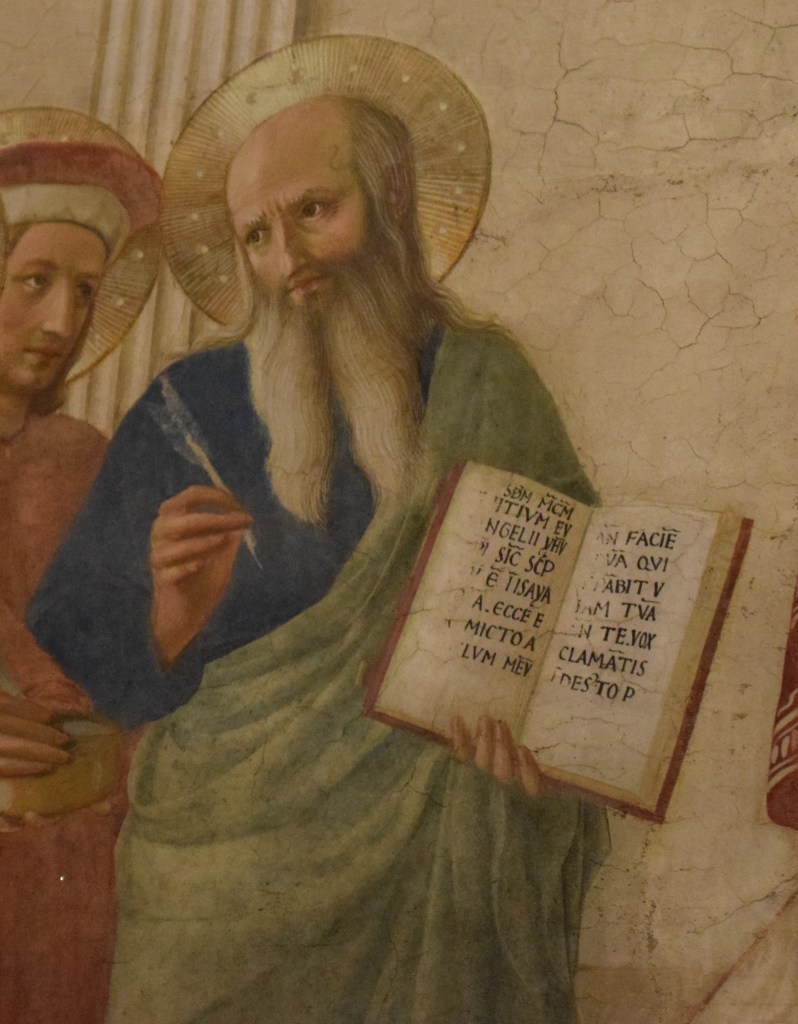

SAN MARCO EVANGELIST (12-68 A.D.) is the dedicatory saint of the convent and its church and titular saint of the Catholic Church. He is recognized by his book of gospels that are attributed to him and his pen, and, also, by the color of his robes – green.

Saint Mark, whose gaze schools San Domenico, is holding a book that harkens to the ‘words of god’ which are believed to have flowed through him, moved his hand, and composed his gospel. The partially eroded excerpt is still legible and, hence, I asked a friend – a polyglot and scholar who is fluent in the three languages of the bible – to translate the Latin words. Here is my friend’s response in toto:

“The first three lines of the Gospel of Mark, 1:1-3, very abbreviated, with misspellings and preceded by the added words SECUNDUM MARCUM,

“According to Mark,” which modify the word “gospel” a few words later.

SECUNDUM MARCUM INITIUM EVANGELII IESU CHRISTi FILII DEI. SICUT SCRIPTUM EST IN ESAIA PROPHETA ECCE MITTO ANGELUM MEUM ANTE FACIEM TUAM QUI PRAEPARABIT VIAM TUAM VOX CLAMANTIS IN DESERTO P[arate viam Domini…]

“The beginning of the gospel of Jesus Christ son of God, according to Mark. As it is written in the prophet Isaiah, “Behold I send my angel before they face, who will prepare thy way, the vox of one crying in the desert, “P[repare ye the way of the Lord…]

The snippet from Isaiah announces the appearance of John the Baptist, seen as the forerunner and “preparer of the way” of Jesus.”

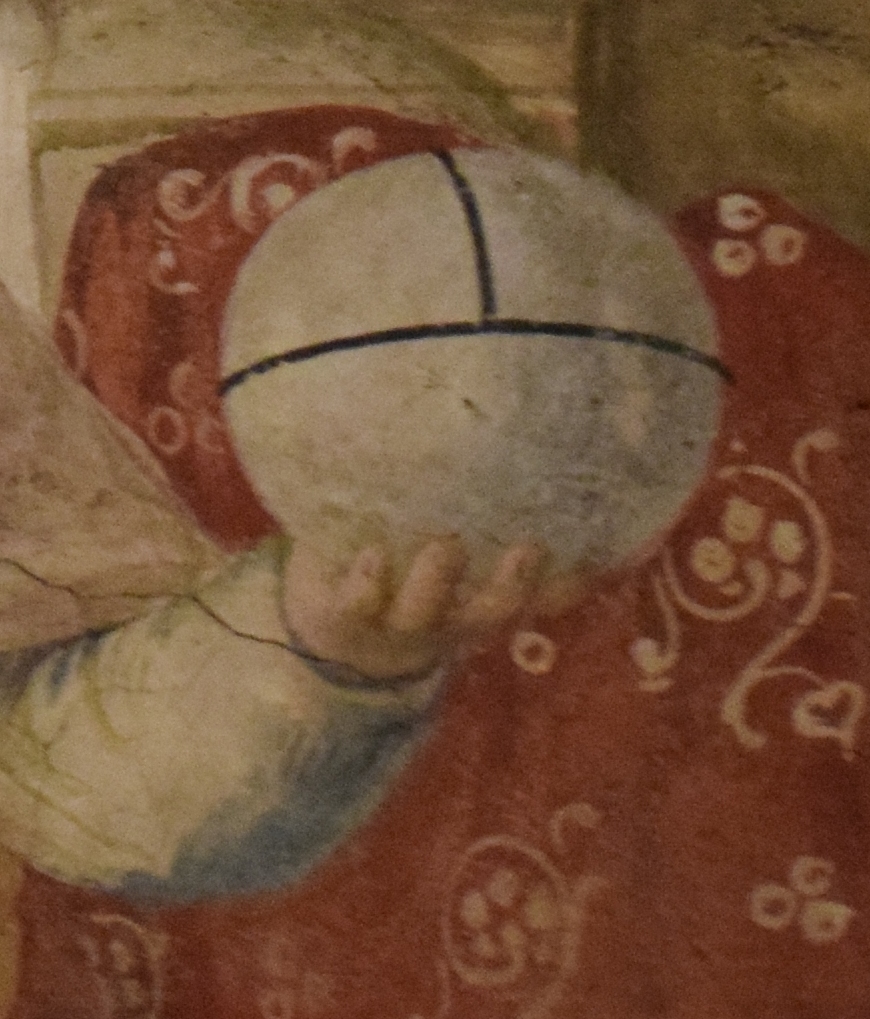

Holding precedence and necessarily central in focus is the enthroned Madonna with a young Jesus sitting on her lap. Jesus holds an orb bearing the stripes of a Globus Cruciger in his left hand and gestures with a blessing using his right hand. His head is illuminated with a tri-radiant halo alluding to the triune godhead of Christianity.

The Globus Cruciger – a cross-bearing orb – in Jesus’ hand lacks the cross normally found on the top which symbolizes his sacrifice and crucifixion. However, because the globe in Jesus’ hand bears the linear divisions associated with the symbol, one might posit that the omission of the cross – intentional to the artist – is meant to speak to the coming sacrifice rather than its completion. Perhaps Fra Angelico draws us into the need to live a Christian life in line with the teachings of Domenico and the gospels in order to experience the triumph of Christianity which Christ’s crucifixion represents – the path to the eternal life promised the faithful. Accepting that proposition, one would be warranted in calling the orb a Globus Cruciger and not a simple ‘ball’.

Mary holds Jesus with her left hand, gazing down on him with a contemplative look that is neither joyous nor truly sad. She presents him to us with her right hand. One needs note that Mary only ever presents the Christian Savior to the viewer is her gestures. Her hands never violate that simple symbolism.

The halo of the sacred mother is illuminated with what might be intended to be points of light and a star shines on the shoulder of her blue robe. The star has eight points and it represents Mary’s title of “Stella Maris” – Star of the Sea – symbolizing her charge as guide of Christ and announcing his coming.

Lapis Lazuli is the cause of the bright, original color of Mary’s mantle. This precious stone, obtained from Afghanistan and ground to a powder to be mixed for a paint, was expensive and used only when a donor had the means to afford its use.

Individually, the second symmetrical group of saints to the viewer’s right are:

SAN GIOVANNI EVANGELISTA (died 99 A.D.), is the protector saint of Giovanni di Bicci de’Medici (1360-1429), father of Cosimo de’Medici, the donor. He is recognized by the color of his robes – pink and by his book of gospels and his pen – the implied words inspired in the same way as those of Saint Mark. Saint John, too, casts his gaze to San Domenico further informing the monk’s calling, commitment, and devotion.

One might propose that the lack of visible text on what is certainly meant to be the gospel of John, which could be seen to ‘unbalance’ the composition, is the result of the precedence of Mark’s words to the convent as it’s dedicatory saint. Hence, the intent of Fra Angelico might be that the unfulfilled text serves to not detract from those words more immediately meaningful.

SAN TOMMASO D’AQUINO (1225-1274), who was a Dominican monk, is identified by his habit and by the gold star on his chest. This brilliant star – an artist’s unicum – can be considered to represent multiple things – the Holy Spirit descending upon Tommaso thus giving him his divine inspiration; a symbol of his wisdom; the light of enlightenment cast by his works and words best measured in his magnum opus the Summa Theologica – become the symbol of his philosophical influence in large.

SAN LORENZO (225-258 A.D.) is the protector saint of Lorenzo de’Medici the Elder (1394-1440) and his name saint. Lorenzo the Elder is the younger brother of Cosimo de’Medici the donor. Fra Angelico depicts Lorenzo with the instrument of his martyrdom – the grill on which he was burned. With artistic preference and freedom, the artist, also, paints Saint Lawrence in the traditional garb of the protomartyr. (The rectangular inset of the robe of San Lorenzo appears to have letters on it. I am consulting an expert to confirm and translate them.)

SAN PIETRO MARTIRE (1205-1252), was the protector of Piero il Gottoso and his name saint. Piero was the son of Cosimo de’Medici, the donor. The saint is recognized by the palm of martyrdom and the blood on his head which symbolizes the manner of his martyrdom – being struck by an ax by the assassin Carino di Balsamo.

This is an astonishing and colorful work that represents saints dear to the Dominicans and to Cosimo il Vecchio de’ Medici, the donor and founder of the Medici family dynasty who has honored both his family and the Dominican order in the commission. Originally, I had planned to simply post one photo of this fresco with a brief explanation of the included saints. But as I became more familiar with the work and each individual depicted, I began to realize that a simple explanation could not do even partial justice to the intentionality of this master work. I am not certain of the completeness of my discourse, but I hope it engenders a greater appreciation of the colors that can both bring delight and yet serve to detract the viewer from the richness of the artist’s narrative. However, to fully appreciate the talent of Fra Angelico and the heart of Cosimo de’Medici a personal visit to the museum is needed. I hope that you find this fresco as beautiful as its long life and fame attests.