As I work on my Wall Madonna photos and their accompanying narrations, I am missing Venice and her beautiful islands of Murano, Burano, and Torcello. My last visit to the lagoon was during the pandemic when Venice was empty of tourists – really! – and very affordable. The city was so affordable that I stayed for two weeks just a few steps from the daily fish market – the Mercato di Rialto. Every day I bought fresh fish for my supper and once witnessed a clever and quick seagull steal ‘pesce’ from a stall. The bird was chased – unsuccessfully – by the owner trying to recover his merchandise! The next time I visit Venice I, likely, will stay in Padova and take the train in – my technique for keeping costs down.

To assuage my nostalgia and to share the beauty of the basilica, here are a few photos of the Duomo of Murano – the 7th-century Basilica di San Donato. I actually missed this church on my three previous trips to the floating city and island likely because the focus in Murano is the fabulous glass furnaces and products there. But this basilica rivals those of Ravenna and Rome. The Cosmati floors and the altar apse mosaic of the Theotókos – the God-bearer – are heart-stoppers. Enjoy the photos and have a great day!

Here is a montage of the basilica: The top photo is of the façade of the church. The façade is crafted after the style of Ravenna – plain and flat. The bottom photo offers a view of the beautiful brick basilica from the Venetian lagoon. This is the back of the church. As with all ancient churches, the altar wall is the east wall so that the worshippers face the east – the land of Jesus’ birth, life, and death.

Murano Island is a short, 10-minute Vaporetto ride from Venice. The comune of Murano consists of seven islands separated by canals and connected by bridges. There are about 4,000 permanent residents. There are no cars on the island. Travel is by foot or bicycle and – of course – by boat.

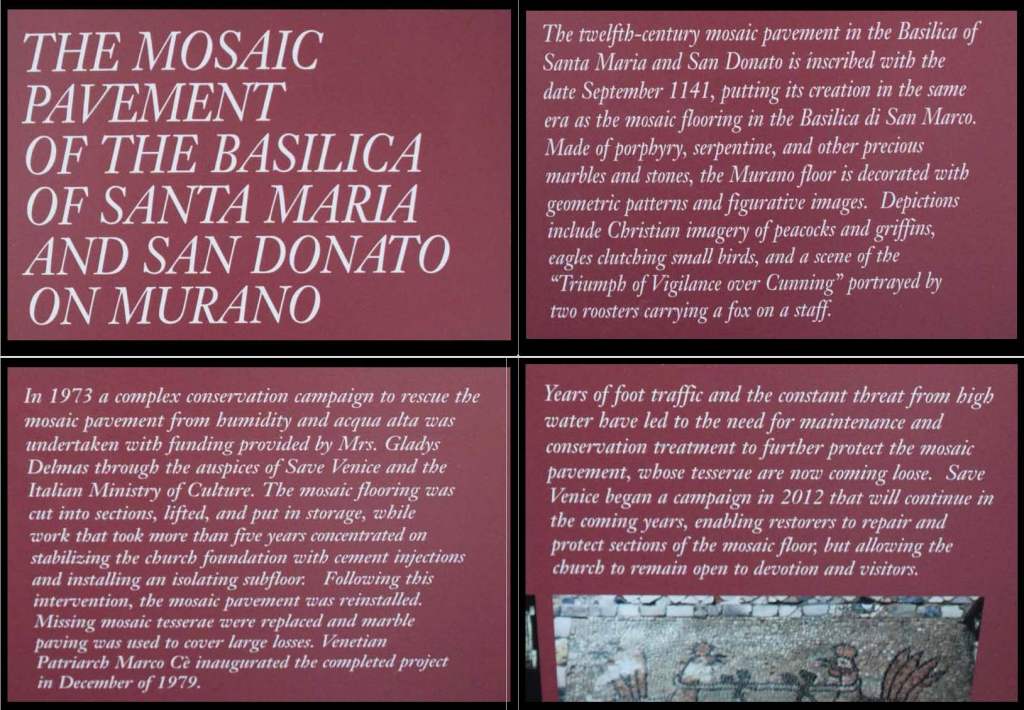

Here is a montage of the 12th-century Cosmati floor mosaics that are dated and ‘signed’ thus: In nomine Domini nostri Jhesu Christi Anno Domini Millesimo CXL Primo mense semptembri indictione V (In the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, in the year of our Lord 1141, in the month of September, in the fifth indiction). FYI: An ‘indiction’ is a 15 year period. The floors were created in the 5th fifteen year period. I have no idea what this means for this specific identification. I only know that this was a method of dating events in the Roman Empire and the papal court. The system was begun by Emperor Constantine the Great in 313 AD and ended in the 16th-century.

The entire floor is allegorical and the information cards in the basilica are fully informative of the meanings. The Cosmati technique was begun by a Roman family who for four generations created these mosaic floors for churches. The work was inspired by Byzantine and Islamic creations that came to Italy through Ravenna and Sicily from Asia.

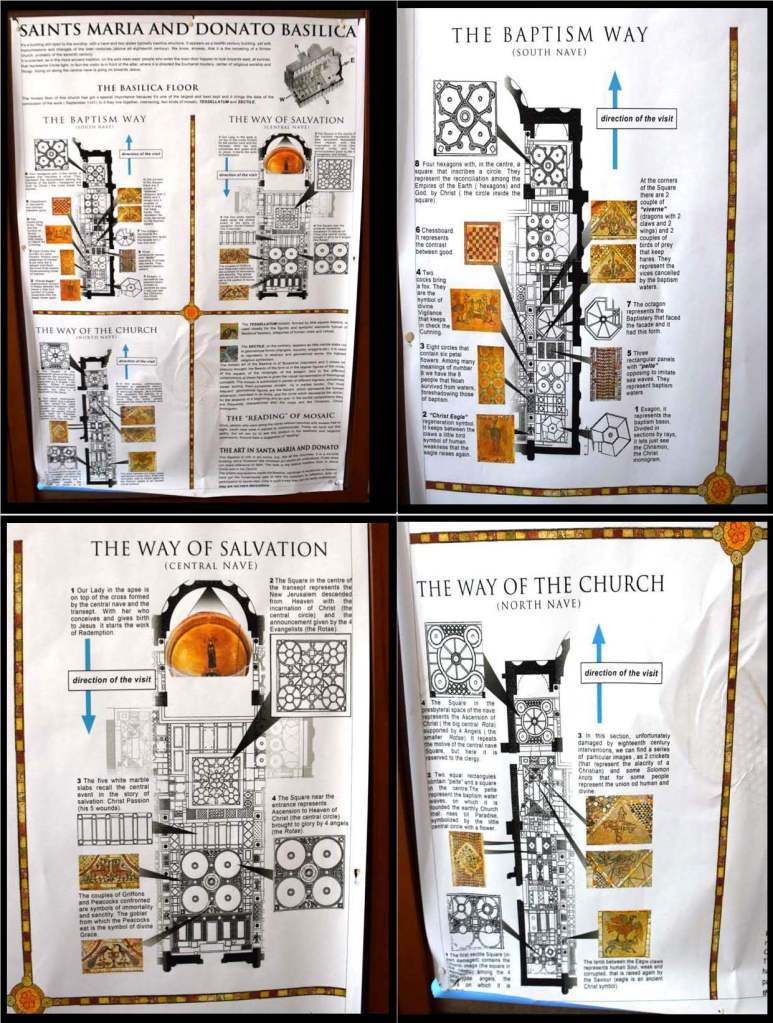

Here is the detailed information offered on the Cosmati floors. There is a pictorial description of the symbolism of the mosaics. I broke the poster into four pieces for easier reading.

Here is another montage of the 12th-century Cosmati floor mosaics showing – from top left, clockwise – the chessboard which represents the contrast between good and evil, the Christ Eagle which is symbolic of resurrection and regeneration, the panel with opposing ‘pelte’ representing waves of water that symbolize the waters of baptism, and the cock and fox which symbolizes divine vigilance that keeps cunning in check.

The original church was dedicated to the Virgin Mary – mother of Jesus. In 1125 the body of the Christian martyr San Donato (died 362 AD) was brought to the basilica from Greece after that island was conquered by the Doge of Venice. The basilica was then rededicated to both saints. In this fantastic full apse mosaic, the Great Virgin is depicted as an orante and identified at the Theotókos – the God-bearer. It is important to note the proper translation of the Greek Θεοτόκος – abbreviated in imagery as ΜΡ ΘΥ – is God-Bearer. Eastern Christianity concedes that Mary was Jesus’ mother in every sense of the word – Jesus has the ‘matter’ of his mother Mary and – as the myth claims – his father God-the father. However, Western Christianity, as represented by Catholicism, calls Mary a ‘vessel’ – a God-Bearer. The myths are silent on Mary’s contribution to Jesus’ human incarnation outside of her ‘sin-free’ womb being the vessel that held him.

Mary is depicted in Byzantine style as an Orante – one who prays and pleads. She is wrapped in a mantle and a maphorion – a large veil worn by Greek noblewomen and often used to clothe Mary and other female saints in Byzantine style Italian art. The stars seen on the maphorion and her mantle are ancient Syriac symbols of virginity.

The description of the mosaic states that Mary stands on a suppedaneum. This is a support for the feet that was used on crosses where people were crucified. However, what she stands on does not look like a suppedaneum to me. But perhaps this is the artistic rendition of this crucifixion component the use of which would clearly be symbolic since nothing in sacred Christian art of this time is accidental. The artists who created the mosaic were Venetians trained in the style of Byzantine art. The style is the same as that of the mosaics in the 9th-century Basilica di San Marco of Venice and the mosaics in the 7th-century Basilica di Santa Maria Assunta on the island of Torcello.

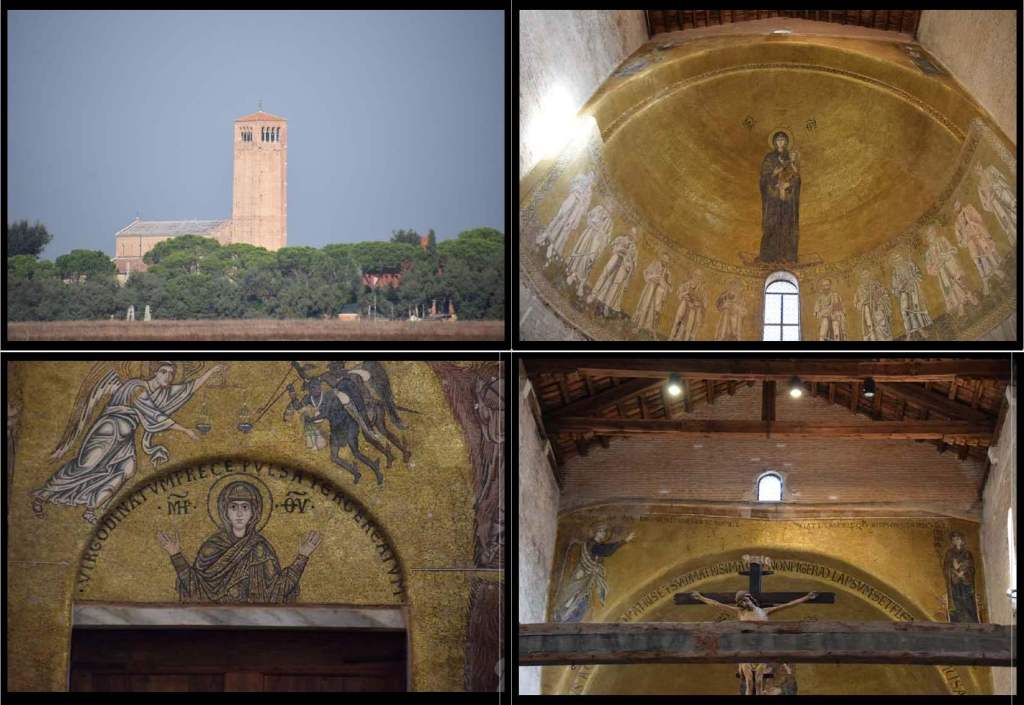

Here is a montage of some of the mosaics of the 7th-century Basilica di Santa Maria Assunta. Clockwise from the top left is a view of the cathedral from the lagoon, the apse mosaic showing the Madonna and Child with the twelve apostles below, the Annunciation of the triumphal arch, and Mary as the Theotókos – the God-bearer in the position of Orante – one who prays. In general, photos are not allowed. However during the pandemic – the time of this visit, the docents were not vigilant. Unfortunately, the lack of light and the gloss of the mosaics make good photos difficult.

This is a dome mosaic (not the front altar) from the 9th-century Basilica Cattedrale Patriarcale di San Marco– the Patriarchal Cathedral Basilica of Saint Mark. As one can clearly see, the image of the Great Virgin is similar in these three basilicas. Mary is depicted in Byzantine style as the Theotókos – the God-bearer in the position of Orante – one who prays. She is wearing a mantle and a maphorion, and her cloak and veil clearly display the Syriac stars symbolizing her virginity. The Great Virgin is flanked by Archangels. The mosaics of San Marco are from the 11th-13th-centuries. One might note that ‘angels’ pre-date the cult of Christianity but the detailed Catholic angelic hierarchy was a more recent 10th-century addition. As with the cathedral of Torcello, photos in San Marco, in general, are not allowed but the pandemic seems to have resulted in a suspension of the prohibition because there was no restriction. However, like the churches of Torcello and Murano, the light precluded photos that did justice to the fantastic golden mosaics – and San Marco is a total golden wonder with its five domes and arches covered in shiny art!!!

Beneath the altar apse mosaic of Mary is a fresco depicting the four evangelists. This is Saint Mark. The frescoes date to the 13th-century.

The cathedral possesses two 13th-century icons of the Virgin Mary. The montage – on the top – shows Mary as the Theotókos and Orante – again painted in Byzantine style. The icon on the bottom is of the Madonna and Child. Because the painting was displayed in a lighted, glass case I had to take a ‘detail’ photo in order that the images not be washed out by the glare of the light on the gold background. The images of Mary and Jesus are adorned with silver and gold crowns to indicate that miracles are attributed to this particular icon.

This is the beautiful open, wooden trussed ceiling of the central nave. The basilica plan has three naves with the central nave surrounded by five marble columns with Byzantine-Venetian capitals.

This is a full view of the central nave from the altar facing west into the open courtyard where there is an ancient freshwater well in the center. I always try to take a photo from the back and front of the church – and endeavor to have the view be as unobstructed by other tourists as possible. However, the light and gloss of the porphyry, serpentine, and precious stones mosaic floor – a full 500 square meters! – washed out all my photos but this one. One can see the beautiful, carved capitals of the columns.

The central piazza or campo of every sestiere in Venice has a freshwater well kept pure and free of salt water by a remarkable ancient system. Venice supplied fresh water using an ingenious method of collecting rainwater – the only unsalted water source for the city. For each freshwater well, a large open space was needed. Hence, wells are only found in the campo’s and piazza’s of the floating city and its islands. The squares were then dug out to a depth of about 6 meters – approximately 20 feet. The excavation was then lined with clay. Next, stones and sand taken from nearby rivers were used to line the clay ‘pits’ – if one can call them that. This made the bottom impermeable or water-resistant. The excavation was then filled. Finally, a series of gutters were built around the well that drained the rain waters from the square into the bottom of the well. The ‘chimney’ of the well itself, beneath the surface of the square, was made of a porous brick that allowed the rain waters – filtered through the layers of sand and stone – to seep into the well and fill it. Water was then drawn out by a bucket. I do not know whether or not any well is still in use – I have never seen one ‘open’. And I have never noticed any system of gutters. Perhaps they have been covered over. This is the freshwater well of the Campo di San Donato.

No church dedicated to the Great Virgin is complete without testament to the signature events of Jesus’ life. Hence, one will almost always find an Annunciation – the Announcement of Mary’s chosen status as God-Bearer by the Archangel Gabriele and her impregnation by the Holy Spirit – through her right ear no less! The triumphal arch Annunciation of the Basilica dei Santi Maria e Donato, sadly, was demolished during 17th-century renovation works ordered by the bishop of Torcello – Marco Giustinian. Many Italian churches lost their Romanesque and Gothic artwork to the imposition of the garish and ornate Baroque style thought to be more modern and more beautiful.

However, the painted altar depicting the dormition of Mary remains for our edification and admiration. The altar dates to the 13th-century. It shows Mary going to ‘sleep’ – the compromise reached by the church fathers who could not suffer either the mother of Jesus dying and then being resurrected – a miracle reserved for Christ – or her not dying and going fully alive into ‘heaven’. Hence, they capitulated and – using the act of sleep as the medium of her deliverance from her earthly life to heavenly one – kept silent on the issue of her death – not a fitting end for the Theotókos – and her resurrection – an inappropriate challenge to a miracle reserved for the deity. The artwork shows Mary going to ‘sleep’ with Joseph kneeling at her bedside holding her hand. She is surrounded by the Apostles. Christ stands behind her bed in a sacred mandorla surrounded by Cherubim. He holds Mary as an infant. The central imagery is flanked by saints. Two saints dressed similarly anchor the far left and right ends. I am not sure who they are but the likely candidates are the twin saints Cosmas and Damien – two Arab physicians who treated the poor free of charge and died as martyrs in the late 3rd-century. Next, I would guess the Bishop of Torcello and Saint Donato are pictured left and right. Finally, one sees John the Baptist on the left and Saint Paul on the right.

This work of art depicts the winged Lion of Saint Mark – symbol of the evangelist and patron saint of Venice. The lion holds the message the saint received from an angel on his way to Alexandria, Egypt: Pax tibi Marce Evangelista meus, hic requiescet corpus tuum – Peace to you, Mark, my Evangelist. Here will rest your body. And true to the words, Saint Mark died in Alexandria. Beneath the lion on the right is the stemma of Murano – a cock with a fox on its back holding a green serpent. The other coat-of-arms represents the podestà of the time – Carlo Quirini. The inscription in Latin reads: Suus Hinc Divo Albano Cantharvus Pendet Tutam Cui Praetor Quirinus Carolus Hanopius Posuit Sedem MDXLIII. This emblem is above the tomb of Saint Albano. A podestà was the person who held the highest civil office of the city. In between the two coats-of-arms is a wooden jar symbolic of a jar that held the wine for the sacred mass. This jar was placed near the body of San Albano in the Church of San Martino in Burano. This symbolic rendering of an ancient tradition was placed here by the mayor of Murano.

No discussion of Murano can be complete without a mention of the artisans whose work endures and makes the island legend. There are about 100 glass foundries in Murano today. This glass-making company in Murano is named after the famed explorer. Marco Polo (1254-1324) – who traveled the Asian Silk Road from 1271 to 1295 was born and died in beautiful Venice – a true Venetian son!

Marco Polo returned from his travels to the state shortly after Venice governors forced all the glassmakers to the island of Murano in 1291 because of fears of fire from the glass ovens. The Travels of Marco Polo – for which he is known – was written when he was imprisoned in Genova – dictated to a fellow inmate – Rustichello da Pisa – and eventually published in French as – Livres des Merveilles du Monde – Wonders of the World Books. As it grew more popular the book became known as The Travels of Marco Polo. It is a fabulous read and, unlike many ‘history’ books, talks about more than war and killing. For example, Polo describes in detail a jeweled artificial mountain built by Kublai Khan that had a tree from every part of his realm planted on it! He, also, discusses the tombs of the Three Magi which he says are in Saveh – a city of ancient Persia south of today’s Iranian capital of Tehran. This claim is contrary to claims that the Magi were alternately held in the Basilica di Sant’Eustorgio in Milan and Germany’s Cologne Cathedral.

The light in the basilica is provided by hand-blown glass chandeliers all made on the island. What seems astonishing and luxurious to the tourist is a common sight in all the churches and buildings of Venice.

I finish this photo narration with an image intimately associated with Venice – and Murano. The beauty of life in the Venice lagoon is best represented by the waters that embrace the buildings and by the canals that serve as the roads of commerce and daily life. I hope you have the opportunity to visit Murano and the fantastic cathedral dedicated to Mary that offers an incomparable view of the ancient past in the mosaics which speak the sacred legends of Christianity.