Because archaeological searches of Morbegno have never borne conclusive – or undeniable – fruit of the town’s ancient origins, it is to the church of San Martino that researchers turned for their evidence and a light to shine into the past.

The road through the Valtellina was a popular trade route as one would expect given the Adda River that flows through the center and the beautiful broad plains that are the feet of the Orobie and Rhaetian pre-Alps that line each side. The valley was inhabited and traveled long before the rise of the Roman Empire which conquered the region around Lake Como and the Valtellina in 16 BC. Christianity began to spread in the 5th-century and as the cult of Jesus and monotheism grew more popular, worshippers began to confiscate old pagan sites of worship by building churches where temples once were. Hence, one will often find that a Christian church – dedicated to a saint – was built on the older site of a pagan temple – dedicated to one of many gods or goddesses.

Thus – regardless building or saint – the site remained sacred space – and magical space imbued with positive forces – to all across the ages. Hence, in Assisi (Chiesa di Santa Maria sopra Minerva) and Rome (Basilica di Santa Maria sopra Minerva) one finds that a Christian church dedicated to the Great Virgin – Mary of monotheistic Catholicism – sits over a temple once sacred to Minerva – the virgin goddess of the polytheistic Romans.

In Morbegno – heart of the Valtellina and way station for journeys to Lake Como – legends from the lips of both those who knew and those who think they know say that Hercules was first worshipped here until the 9th-century where Saint Martin now is courted in the 21st.

And so just like that – Saint Martin of Tours – Roman soldier and Christian convert – champion of the poor and beggars replaced Hercules – Roman warrior and half-god – champion and protector of the weak. And a church was built where a temple once stood. Truly one must agree with the intentionality – and smartness of these choices – virgin for virgin and warrior for warrior – all protectors of the humbled masses. The holy place remains holy and the faithful need not admit to change. Such is the magic and charm of Italy, and why one visit to such a place is never enough to fully grasp the wonder of it!

The church of San Martino dates orally to the 9th-century and conclusively in text to the 13th-century. The remains of the ages that greet a visitor today come from the renovations performed in the mid-1500’s to the early 1800’s. Local artists were employed. Vincenzo de Barbaris who authored the beautiful enthroned Madonna and Child on the north wall was an early 16th-century Valtellina transplant for Brescia near Milan. This commissioned, more ‘modern’ fresco was placed on top of a previous fresco painted during the Romanesque age of the church.

The two men who frescoed the presbytery in 1575 hailed from Lake Como – Francesco de Guaita was born in Como and Abbondio Baruta lived and died in Domaso.

Art historians and experts say that the work is in the style of Lombard Mannerism. As to what that is – well – I am not quite sure. However, from multiple definitions of three characteristics – none of which are precisely rendering in words – the one common attribute I can find is the flattening of the decorated space. In other words, the filled space around the figures lacks a 3-dimensionality. I cannot say what is meant by this because the imagery does have a multi-dimensional characteristic. I can say, however, that this is, in a way, haphazard and not executed with the geometrical precision of – for example – a Piero della Francesco (1412-1492).

Every inch of his paintings is in perfect 3-dimensional perspective. Yet the presbytery frescoes of San Martino are beautiful and wonderfully colorful and the artists were clearly talented. Sometimes trying to learn more about a thing robs it of its wonder! I do not understand what Lombard Mannerism is and I love these frescoes!

When a new altar piece was needed an artist born in Caspano – a village directly across the river over the beautiful Ponte di Ganda and 900 meters up in the Rhaetian pre-Alps – who carried the lineage of those who settled that beautiful mountain town – was chosen. Giacomo Paravicini known throughout his career as Il Gianolo was born in Caspano in 1660. He was a talented and respected local artist. His renown brought him numerous commisions. For example, he painted frescoes in local churches in villages such as Caspano – the place of his birth, and the mountain towns of Cino, and Cercino. Giacomo died in Milano in 1729 leaving four children two of whom became painters and carried on the family profession.

The previous montage shows the Ponte di Ganda which one had to cross to reach the mulatierra or sentiero leading to Caspano. The current bridge was completed in 1778, replacing the original bridge from the early 1500’s. On the right is the view from the belvedere of the Caspano parish church, the Chiesa di San Bartolomeo. It is easy to see why the Paravicini patriarch – Domenico Paravicini – escaping the war between the Guelphs and Ghibillenes, in 1250 took all his possessions and chose this mountain town for his home!

The Paravicini altar painting shows Saint Martin cutting his mantle with his sword in order to give half to a beggar. This is the act of charity for which he is known. A comparison of this work to the style of the work of the surrounding frescoes shows the changes taking place in the depiction of the holy personages who are posed more naturalistically rather than the flat, but more biblically descriptive and ethereal poses one finds in the 15th and 16th-centuries. One, also, might take notice of the changes in color from a bright to a more muted palette.

The organ seen on the south or right wall of the church was taken from the Church of Sant’Antonio in Morbegno in 1801. The Chiesa di Sant’Antonio was once a monastery and is now publically owned and used as a venue for cultural offerings. The original cells and other rooms of the monastery are used as practice rooms for music and dance. It would seem that this change precipitated the transfer of the organ which one can assume was no longer needed.

The Chiesa di Sant’Antonio was built in the 15th-century. Like the Chiesa di San Martino, the interior of the church was frescoed by local artists – Alvise de Donati (Montorfano, 1450 – Como, 1534) and Vincenzo de Barberis (Brescia, 1490 – Sondrio, 1551) – the artist who painted the enthroned Madonna & Child of San Martino.

The mid-19th-century ceiling motifs of the three naves were the work of the Morbegnese artist Angelo Greco. The monochrome ceiling art was commissioned in 1842 by local emigrants to Rome who called themselves the “Consorzio dei Benefattori in Roma dei Fedeli Defunti della Chiesa di S. Martino” – “Consortium of Benefactors in Rome of the Deceased Faithful of the Church of St. Martin”. To be informative – the identifying feature of monochrome painting is the use of only one color.

In front of the chapel to the left of the altar is the 1643 tomb of Tomaso Paravicini. The literature on the church says that in the floor are eight large tombs – one used to bury the priests and monks of the church and monastery, one used to bury men, one used to bury women, three used for the families of important members of the parish, and two used for members of the Paravicini family. Six of the tombs are not identified with any carving. They are simply large ‘squares’ in the floor of the church that are removable. They are flush with the floor and identifiable as coverings that are able to be removed.

I found this tomb in the floor under a pew. The name on it is Gioan Etro Casal 1702. The tombstone has not been damaged, altered, or truncated in any way. Although the custom for tombstones is to list the surname first followed by the sequentially ordered first and middle names, I was not really sure about this name. All three names are surnames – the first – Gioan – is French or Belgian, the second – Etro – is Italian, and the third – Casal – is Spanish-Galacian. All three names are found in an Italian surnames map with Casal being the most frequently found. After an extensive search I learned the tomb is for the family of Gioan de Casalis who was known as Perini.

I include these two photos for two reasons critical to researching the artifacts found in an ancient building. The first photo shows that what seems a perfectly logical assumption about a historical remnant may be quite incorrect. This tomb is not for one person. It is for the family members of this particular patriarch. The second photo of the de Casalis family tomb is an example of the difficulties one can face when trying to understand an inscription which has not – as far as can be discerned – been altered. The name Gioan Etro Casal is far removed from de Casalis and certainly not at all relatable outside of other evidence to the name Perini and the name is not ordered as would be expected with surname first. There is always something interesting to be learned!

The Chiesa di San Martino has been a cemetery church since the first round of renovations that erased the Romanesque art of the early 1200’s and replaced it with the evolving early Renaissance art of the 16th-century. And unlike many ancient cemetery churches in the Valtellina that are kept closed to preserve their precious art and frescoes, San Martino is open every day.

Here are the best of my photos of the church interior. I hope they bring you joy and motivate you to a visit!

This fresco of San Lorenzo – Saint Lawrence – was painted by 1575 by Francesco Guaita from Como and Abbondio Baruta from Domaso. San Lorenzo (225-258) is the patron saint of librarians and archivists – the result of his efforts to hide important church documents from those who would destroy them. The image of San Lorenzo flanks the central altar painting to the right of it. Saint Lawrence’s gaze is directed at the Saint Martin – the central alter piece.

The view that accousts the eyes on entering the small church. The church has three naves. The center nave is lined with ancient stone columns giving the worshipper a focused view of the elaborate marble altar with its Baroque pillars framing the Giacomo Paravicini altarpiece painting of Saint Martin. The presbytery and altar are on the east wall. As with all ancient churches, the worshippers face east toward the land where Jesus was born, lived, and died.

The presbytery fresco cycle painted in 1575 by Francesco Guaita from Como and Abbondio Baruta from Domaso recalls the signature events from legends of the life of San Martino. On the south or right wall just inside the presbytery, is a large mural of Saint Martin in Trier, Germany preaching against the Arian heresy. The fresco to the left depicts Mary Magdalene with jars of ointments and myrrh. The fresco in the lunette above shows Jesus speaking with the Samaritan women – a legend found in the biblical book of John.

For those interested, Arian Christianity rejected the claim of Jesus’ divine equality with God the Father. The belief was that Jesus was created by God and not equal to Him – Jesus had a ‘beginning’. He was not immutable. This belief undermined the concept of the Trinity and was thought to reduce Christian monotheistic beliefs to polytheism. The Trinity is the Christian doctrine that holds that there is one god but that he exists as a triune godhead with three immutable and equally divine persons.

This fresco and its accompanying lunette and flanking fresco of Mary Magdalene are interesting for their pairings. Saint Martin is in Germany speaking to the people and doing missionary work as a fisher of souls. In the lunette, Jesus is the missionary and fisher of souls speaking to a Samaritan woman who was not a Jew and did not follow him. He acted to convert her to his word as Saint Martin acted to convert the Arians.

Mary Magdalene is called the apostle of the apostles who understood Jesus’ word best of all his disciples. She is considered a hero of the faith. Jesus was the apostle of God – the ultimate purveyor of God’s word. He is a hero of all humankind in his teachings and sacrifices. The mindfulness of the artists in juxtaposing these two hagiographies showing actions in imitation of the works of Jesus is a wonderful thing to come to understand!

This is a fresco of the proto-martyr – Santo Stefano. Santo Stefano (5-34 AD) was stoned to death. One can see the manner of his martyrdom represented by the stone seen near his head. A proto-martyr is someone who is the first martyr for a cause. Saint Stephen was the first Christian martyr. The fresco is located on the east of front wall to the left of the altar. Saint Stephen’s gaze is directed at the altar painting image of Saint Martin.

The presbytery apse ceiling fresco of the Agnus Dei is beautiful. The Lamb of God lies on the book of the Word and holds the cross of crucifixion. He is surrounded by angels holding the tools used to crucify Christ. Additional angels hold the Veil of Veronica with its ‘divinely’ imprinted face of Jesus and another holds Jesus’ tunic. The imagery is especially moving.

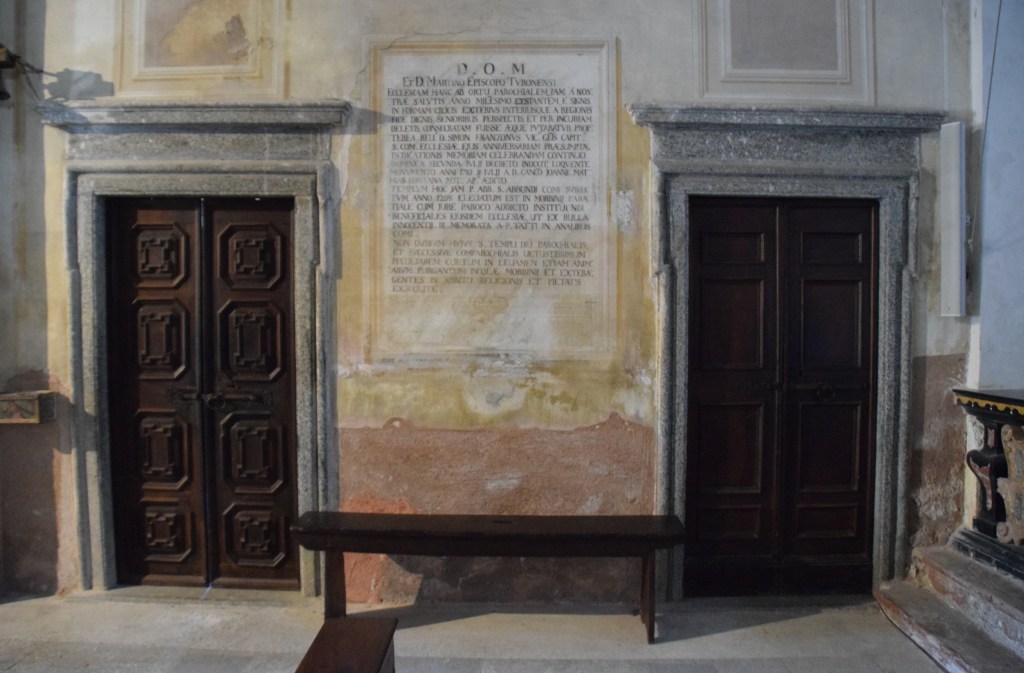

These are the doors on the south or right wall of the church. They lead to the internal rooms of a later annex added to the original single, rectangular structure. In between the doors is the 18th-century dedication of the church offering information of its first Christian 13th-century origins.

In this paired mural on the north or right wall just inside the presbytery, is seen Saint Martin performing the miracle of resurrection when he renews the life of a dead child. The fresco to the left depicts Saint Catherine of Alexandra. The fresco in the lunette above shows Abraham about to kill his son Isaac – being more loyal to a command from his God than to his own child.

This is not a biblical legend that I find instructive unless the instruction is to mothers to hide their children from their murderous fathers. Frankly, if God told me to kill my child, I would have told Him to do it Himself!

However, the three frescoes – true to Christian myth – are fascinating when considered for their inter-relationship. The central fresco depicts a saint raising a child from the dead. This is one of the miraculous legends for which Saint Martin is known.

The lunette is focused on Abraham – to whom three religions are traced – Judaism, Christianity, and Islam – and who was a prophet and saint. The interpretation of his sacrificial act – the intended slaughter of his child – varies among the religions. However, all three faiths link the sacrifice to adherence to the commands of god and each represents a type of resurrection – where faith earns resurrection and renewal through the act of obedience.

The flanking fresco depicts Saint Catherine of Alexandria with the wheel on which she was tortured and that which crumbled at her touch being no match for her faith. Catherine – who was eventually beheaded – was an 18-year old martyr from Egypt – a child who chose death in adherence to the tenets of her religion. In her death she was resurrected in the promised afterlife.

The fresco of a dead child resurrected is paired with a fresco of a living child about to be sacrificed for the faith of his father and another child martyred because of her faith. All three ‘children’ live again as a consequence of the actions of faith. As with the fresco on the opposite wall, the collocation of the myths speaks to the theological understanding of the artists and the satisfactory completeness of the religious lesson rendered within the boundaries of the space is testament to their talents.

This is the second of two cherubs each above the fresco of a saint flanking the altar painting of San Martino. This cherub floats above the head of San Lorenzo and – on the opposite side of the altar – the other floats above the head of Santo Stefano. In the Catholic ninefold, angelic hierarchy cherubs are the second highest rank following behind the seraphim. In antiquity, cherubs were represented as having a double set of wings, long, straight legs, hooves instead of feet, and four faces – an ox, an eagle, a lion, and a human. Western Christianity transformed cherubs into chubby, flying boys.

This is a partial view of the frescoed sub-arch and inner presbytery wall. Seen here is a close detail of the lunette of the south wall with a visual portrayal of an encounter discussed in the book of John: 4:1-42, where Jesus talks to a Samaritan woman. The full photo shows the artistic flow and coordination of the biblical myths: saints line the underside of the sub-arch with an angel in between each, the mural of Saint Martin is capped by the lunette of Jesus and the Samaritan women. Surrounding the lunette are the angels that serve the Agnus Dei of the altar ceiling apse.

This is the marble floor of the presbytery laid in a Escheresque geometric pattern. The floor dates to the 16th-century renovation and is made of the black and white marbles quarried from villages on Lake Como.

Next to the fresco of Santo Stefano on the adjoining south wall is a fresco depicting San Martino curing an old man whose body was covered with sores.

This is a partial view of the ornate, Baroque altar made of many colored marbles quarried throughout Italy which was paid for by emigrants from Naples. The inscription reads: NEAPOLIS ET PATRIAE SUFFRAGIIS. My best guess at the translation is: Naples and the Patriot’s Suffrage.

I like this view of the cemetery from behind the entry doors of the church. I find it interesting that doors are decorative only on the exterior side – the side that faces the visitor – or interloper. One might wonder what language the unembellished interior doors speak. Certainly the beautiful wood panels decorated with brass nails tongue the sentiments of welcome – or warning – of the proprietor. But what are we told when facing the neglected counter-façade of the portals?

This small fresco of San Martino that is located on the front of the church on the left side of the entry doors is said to have been painted over an older image of Saint George the Dragon-slayer. Saint Martin and Saint George were both soldiers and it is common to see them both depicted in a church. When the church was dedicated to Saint Martin, his effigy replaced any of Saint George. In this small and eroded fresco it is still possible to see that the saint is dressed in Renaissance clothing – garments associated with the time period of the artists. I really like this representation which normalizes the saint by conforming him to the norms of the time thus making him more relatable or relevant to the worshippers. The clothing also abides the changing tastes of artistic imagery where holy persons, saints and deities were being rendered more naturalistically.

When one steps outside the church, one is within the walls of the Morbegno cemetery. This photo shows a view down the side of the large, three-sided mausoleum that encloses the garden of cemetery tombs with their upright headstones. A tomb is a grave located beneath the earth. A mausoleum is an above-ground grave. Italian cemeteries are very well kept. It is rare to see a gravesite lacking flowers.

This is a view of the newest side of the expanding cemetery. Because death is relentless, cemeteries grow. But because Italy does not have the space and since cemeteries located in cities often have no space to grow, accommodations are made. The bones of the members of a family might be dug up, collected, and placed in a single grave. The tombstone then may list only the family name and offer photos of the deceased. If there is space the stone will list the name of all those interred there. The photo on the grave markers may or may not be true to the age of the individual at death. For the foreign visitor trying to locate his or her ancestors in an Italian cemetery the practice of putting pictures without names on a tombstone is not helpful. Regardless, in this photo, I like the image of Jesus with a crown of thorns amidst the many pictures of the dead commonly found on Italian tombstones. It looks like a garden of faces!

This fabulous epitaph introduced by a skull and cross-bones above it is on the front of the church hovering over the entry doors. The chilling poem makes the dedication of the church to the cult of the dead unmistakable. The words are a clear admonition – a fitting message of mortality from this church the doors of which lead to the land of the dead!

I AM DEATH UNQUENCHABLE IO SONO MORTE INSAZIABILE

MY SENTENCE IS DREADFUL IL MIO MOTTO E FORMIDABILE

I GO ON FOR ALL ETERNITY IO COTIN[U]O SEMPITERNO

EITHER IN HEAVEN OR IN HELL O NEL CIEL O NELL’INFERNO

Because my focus is Wall Madonna’s I end this presentation and pictorial narration with a Wall Madonna! This beautiful ascended Madonna and Child belongs to the mauseluem alcove of the Gadola family. For them, I hope many years pass before a name is added to the red granite stone! For all of you, my hope is that you enjoyed the art! Art is a social construction that exists within the boundaries of a society and culture. There is no artist whose hands are not moved by the norms inculated and assumed through a life steeped in social interactions. The implcit understandings that motivate us become explicit in a work of art. Art is a social act. Art is us.