Andalo Valtellino is a small town on the Orobic side of the Valtellina that lies at the mouth of the Lesina Valley. Resting between the villages of Rogolo – to the east, and Delebio – to the west, its antique heart nestles on the toes of the Orobie pre-Alps where the backs of its remaining ancient stone homes brush the stone of the mountains and spread like arms from its parish church.

So situated at maximum possible distance from the plains of the River Adda, Andel – in the Valtellinese dialect – is now fronted by an industrial area with its modern, restored homes on the flat of the river plain behind the warehouses of those aziende, and the old, mostly unoccupied, stone homes hugging the mountainside and embracing the parish church. Thus, the marriage of the urban old with the urban new – for the villagers – results in a view of the valley painted by the expansive roofs of the sprawling metal and cement ‘magazzini’. To restore the vista and melt the ugly factories into the colors of nature, a climb to the summer pastures of the Lesina Valley is required.

From both sides and behind the 17th-century church are old mulatierre – still paved in stone and in good shape that – along with a restricted-passage road – a strada agro-silvo-pastorale – lead steeply into the alpine valley and the old meadows that were important summer pastoral areas for residents and their livestock. Andalo Valtellino – with a name shared by the valley in which it abides – feels old and cozy. When walking here it is easy to imagine a peasant camaraderie filling the air with the melody of life and the sweet and sour smells of hay and manure. There are old Wall Madonna’s to be found in the village – most from the 18th-century – and more to be found on the walls of the summer huts of the localita’s Piazz, Avert, and Revolido.

Here are some views of the mulatierre that begin in Andalo and criss-cross the mountain face all leading to localita’s from 500 meters to over 1000 meters above the valley. These stone-paved roads tend to be very steep making the walk up them heart-pounding and the walk down slippery and difficult.

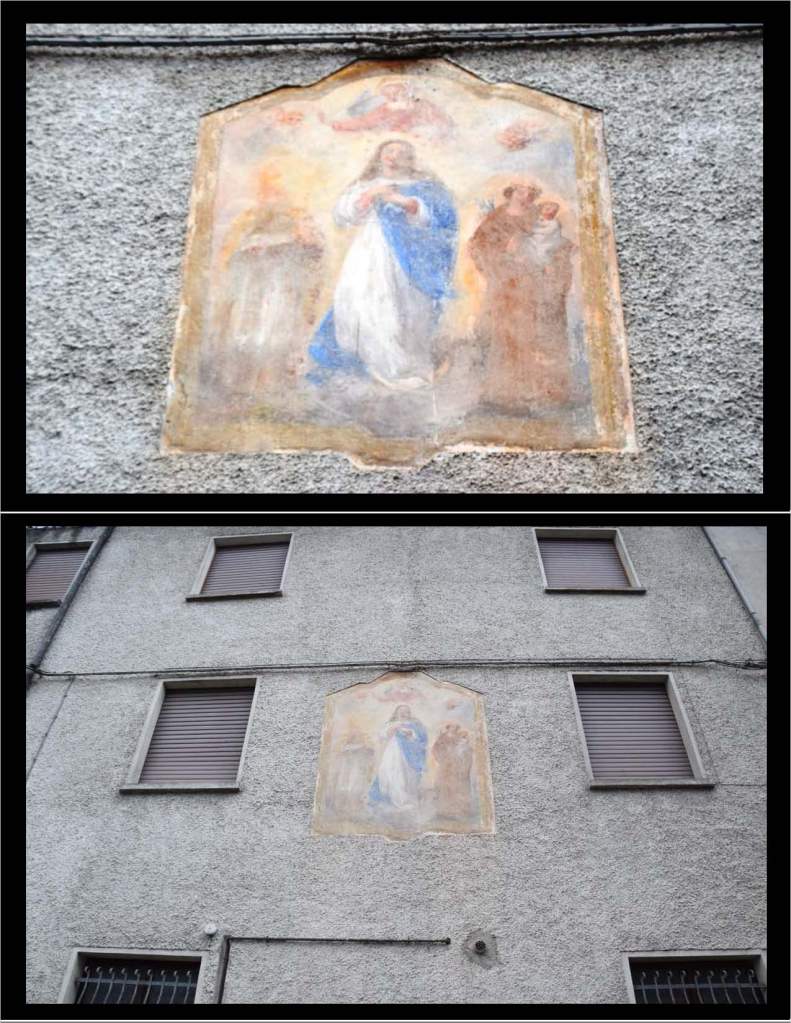

These eroded but once lovely frescoes were executed in the 1700’s in a time that harkened to the voice of a better future. In 1602, the parish of Andalo Valtellino along with its eastern neighbor, Rogolo, broke from the jurisdiction of Delebio. Soon after, the Valtellina was accosted by the mercenary Lanzichenecchi – Protestant German soldiers in the hire of the Three Leagues – who came to the valley bringing murder at the ends of their pikes and death with the ‘mortenera’. The plague they brought in 1630 killed more efficiently than their swords and decimated the entire valley in two years killing one-third of the population of Delebio, Rogolo, and Andalo.

In their wake, the men – the Lanzichenecchi – whose economic prosperity was bought with blood, rendered destroyed the peace and lives of the people, and many of the sacred images frescoed on the walls of houses and churches, which their religion did not recognize with respect and whose destruction it, thus, sanctioned. Hence, one finds here the 18th-century remains of Wall Madonna’s whose origins flow forward from that time of death to a time of renewed life and prosperity and hope for a continued bright future. The colorful paints of most of the frescoes are lost to erosion leaving empty yet still sacred spaces on old homes. The ones that remain I have done my best to find and capture with my camera.

Because I have only walked to Piazz, what I offer here are those frescoes found in that localita’ at 466 meters above the valley and in the valley floor village of Andalo Valtellino.

This is the strada agro-silvo-pastorale that leads into the mountains. These restricted passage roads belong to and are maintained by the comune. People with homes in the mountains pay a small, yearly fee for unlimited access while all others pay a municipal toll of a few euro’s to drive them for a day. However, walking the roads or biking them is free. These ‘strade’ are often intermittently paved, very narrow, steep, largely without guardrails, and unpleasant to drive. But the rewards of nature and the beautiful views are worth the traverse as is, of course, feeding one’s curiosity. To the left in the photo above is the parish church – the Chiesa della Beata Vergine Immacolata di Andalo. One can see that the building was worked into the slope of the mountain. In the photo below is a glimpse of the quality of one’s drive up the mountain face.

This is Piazz or Piazzo as one finds on a map. The huts of this localita’ of Andalo Valtellino are clustered together around a small central piazza. Being the only relatively ‘flat’ expanse here perhaps motivated the name. This small borgo lies at 466 meters and most of the homes have been restored. There are meadows surrounding the houses and – although steep – the terrain and dirt paths in the surrounding forest allow for relatively easy walking.

The restored Madonna and Child picutred above is colorful and only hints at the talent of the artist who first painted the images. This fresco is located above the entry door to one of the homes of Piazz. The complete inscription is not viewable but what can be seen and the image coupled with the clear identification of the Lake Como town of Dongo indicate that this is a copy of the Madonna della Lacrime. The viewable inscription reads: BV DELLE LAC… DONGO – M.B. This implies the complete inscription is thus: Beate Vergine delle Lacrime – Dongo – M.B., and translated would be Blessed Virgin of Tears. The initials indicate the donor who most likely owned the original house. The Madonna delle Lacrime is an early 16th-century painting that ‘cried’ – as the legends claim – in 1553. The original painting is found in the Convento Francescano Madonna delle Lacrime in Dongo. The miraculous work has been imitated in many Wall Madonna’s throughout the Valtellina and the lake region.

This is a view of the surrounding alps seen from the meadows of Piazz. It is my opinion based on the low altitude of this localita’, the urban design of the tiny village with all the homes clustered together in a center marked by a piazza with a shared bank of well-built and multi-functional barns behind, and the beauty and landscaped nature of the surrounding meadows that, in the past, these small homes were occupied year-round.

This Wall Madonna, also found above the entry door of a home in Piazz the front of which faces the piazza, is likely 18th-century originally but eroded and replaced with a more modern image of the Madonna and Child.

The date of 1732 with a cross indicating the home of a Catholic adherent is carved into the header of the door of an ancient home. This home was not restored for residency but was restored to functionality.

This is a modern Sacra Famiglia placed on a home built in 1850 and restored by the family in 2000. The home has the best view of the valley in the small village and is beautifully decorated with wood into which are carved personal messages about the family and home.

This is a beautifully restored 19th-century home that hosts the modern Sacra Famiglia pictured and described previously. At the top is the story of the home. In the full-frame, one can see my walking stick, sweatshirt, and camera bag. I only carry one walking stick because in my other hand is my camera. The story carved in wood is in the Valtellinese dialect. I will add the translation soon!

This is the view of the village from in front of the barns. The dirt path leads down to the small shrine dedicated to those lost in WWI and WWII. The shrine is beneath the village on the cliffside.

The Tempietto degli Alpini built and dedicated in 1999 is an open-front shrine with a small belltower and a room that can be used by the local Alpini Group – the Grupo Alpini Andalo. The shrine is dedicated to the men of Andalo Valtellino who died in the two world wars. The frescoed Madonna and Child is bright with gold and very beautiful. She is a dark-skinned Madonna after the Orthodox style and the style popular in Sicily – a place to which many Valtellinese men migrated for work in the 15th to 17th-centuries. The Black Madonna – as she is called – symbolizes strength and power and this image was likely chosen to speak to the character of the caduti – the fallen who died fighting in the wars.

This is a view of Piazz from the meadow behind the village. There is no parking up here, and no easy road into the village. One must walk up a narrow path that leads from the carriage road and old mulatierre.

Back in Andalo Valtellino and on the road that leads into the mountains is a wonderful shrine of the Virgin ascended. Shrines such as this are always found along the mule paths that were the ‘highways’ of old. This shrine was restored in the Marian Year 1954. It is telling of the devotion of the town that this lovely shrine was how the people abided the papal proclamation that declared 1954 the first international Marian Year in the history of the Catholic Church. A Marian Year is a calendar year that a religious leader declares to be a year that the Great Virgin – specifically – is to be celebrated and acclaimed. In 1953, Pope Pius XII made 1954 a Marian Year in his encyclical Fulgens Corona (Radiant Crown). The year 1954 was the 100-year anniversary of the written stipulation of the details of the church dogma declaring Mary to be of Immaculate Conception – conceived and born free of ‘original sin’ – the church teaching that all are born with the sin of Adam and Eve. The theological position on Mary’s conception has long been debated by Christians and only the Roman Catholic Church has made it specific and its belief a required matter of faith. The dogma is rejected by Protestants and the Eastern Orthodox Church. The Great Virgin is the commonly chosen saint for intercession against the plague and other illnesses and woes. It is some variety of her image that one finds all over the Valtellina.

This carefully guarded Wall Madonna shows the Virgin and Child enthroned with two saints on the left and one saint on the right. Although quite eroded, the saint on the right seems to be Anthony the Great – the abbot. The saint to the far left might be Saint Anthony of Padova and the saint next to him may be Saint Joseph. However, these are guesses. The once elaborate and informative dedication is too eroded to read. I found this fresco on a street close to the boundary of the town situated on what was once a home but is now a barn.

This is a trough for livestock. The water is clean and can be drunk but the construction was for the livestock kept in the village barns. The restored trough is dated 1903.

Above is pictured a modern crucifixion that replaces the lost Madonna that occupied the part of a former wall next to the old entrance to a home. The space is always sacred and – if not left bare – is populated by a new image.

This is one of the homes that rests against the mountain. The stairs lead to the homes next to it that also rest against the slope and are on different levels but in a long line fronted by a cobbled lane. The lane is wide enough for small cars and these homes are multi-storied with many small apartments most of which had to be reached by ladders that gave access to the different levels. Mostly unoccupied and some in very bad shape, one finds the occasional restored ‘section’ with a door like this – indicating a resident.

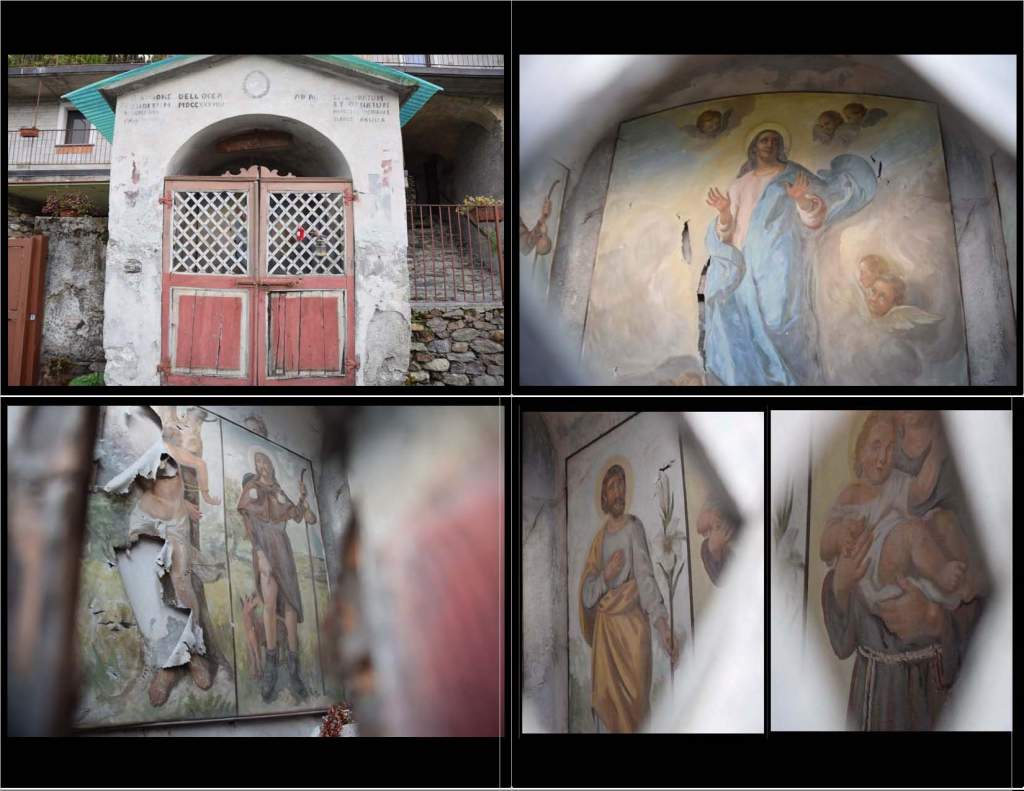

To the left of the home in the previous photo and near the end of the cobbled lane that merges into the old road that travels laterally to Rogolo is this still lovely but difficult to view Madonna shrine built in 1739. Inside one finds a Vergine Assunta with Saint Sebastion and Saint Rocco to the left and Saint Joseph and Saint Anthony of Padova to the right. This is a plague Madonna – one that seeks intercession against the Black Death. This is the oldest part of the town. The once very beautiful and ornate shrine has been restored with the flanking saints painted on hard medium and installed over the original frescoes. Even the restoration is deteriorated. The door cannot be opened due to rust and the warping of the wood. I think the doors are a later addition. The photos are the best I could do between the cracks and the lattice. The original inscription remains and lists the author’s name and date of construction to the left and the donors’ names to the right. From what I can see and translate – the original donor was a Dell’Occa and the date 1739. And it seems the shrine is in memory of Vittorius Margolio and Ancilla Girolo Ancilla. I asked a friend who is an expert in Latin and reconstructing dialects to translate the inscriptions. Here is his entire reply:

I puzzled over this one, mostly over whether to read each side separately or whether to read across for left to right, then back to left, and to right, etc. It’s mostly in (shaky) Latin with some Italian and some “hybrid” (Victorius = Vittorio).

Your inscription is very difficult to read, but I magnified it and this is what it says.

On the left:

A SIMONE DELL’OCCA

CONDITUM MDCCXXXVIII

MEMORES NUNC

V AUG MCMLXIV

On the right:

AB ANT. RESTAURATUM

ET ORNATUM

MARGOLFO VICTORIUS

GIROLO ANCILLA

The “missing” understood word, to which everything else applies, is AEDICULUM (Modern Italian, edicola). In ancient Rome, where the word for house was aedes, an aediculum was a shrine, a “little house” that the family had in a prominent place in the equivalent of the parlor, in which they put little statues of the gods and goddesses their family was particularly devoted to in front of which they put flowers, lit oil lamps and burned incense. Christians in the Roman empire, put crosses and icons in their aedicula (pl. of aediculum) and also put flowers, lit oil lamps and burned incense. Later on, aedicula were enlarged and constructed outdoors, becoming the roadside mini-chapels you see everywhere in Italy and Greece.

AEDICULUM is a neuter singular noun in Latin. So the adjectives CONDITUM, RESTAURATUM and ORNATUM, all neuter singular, refer, obviously, to the AEDICULUM.

So, this little chapel-shrine was built (1739), then restored and decorated (at some point). The question is the role of the four persons mentioned in the inscription. You have:

Simone Dell’Occa

Antonio [Dell’Occa]

Vittorio Margolfo

Ancilla Girolo

And then there is a second date. Referring to what? And what to do with the adjective MEMORES, which is nominative m./f. plural?

A SIMONE DELL’OCCA

CONDITUM MDCCXXXVIII

Built by Simone Dell’Occa in 1739

AB ANT[ONIO] RESTAURATUM

ET ORNATUM

Restored and decorated by Antonio [Dell’Occa]

MEMORES NUNC

Remembering [them?] now

MARGOLFO VICTORIUS

GIROLO ANCILLA

Vittorio Margolfo [and] Ancilla Girolo

V AUG MCMLXIV

[Dated] August 5, 1964.

The only thing that leaves me a little unsure is the word ANCILLA. In Ancient Rome, an ancilla was a female house slave. From Christian antiquity through the middle ages and the Renaissance, ancilla meant simply “maidservant,” the female analog of “manservant.” When handing communion to a female parishioner, a Latin-speaking priest uses the formula: Ancilla Dei, Virginia, accipe corpum Christi, “Handmaiden of God, Virginia, receive the body of Christ.”

I can see Ancilla just being a first name. But I also wonder if, in 1964, the inscriber (whose Latin wasn’t great) might just have thought it was a fitting word for “wife” or “helpmeet,” something like that.

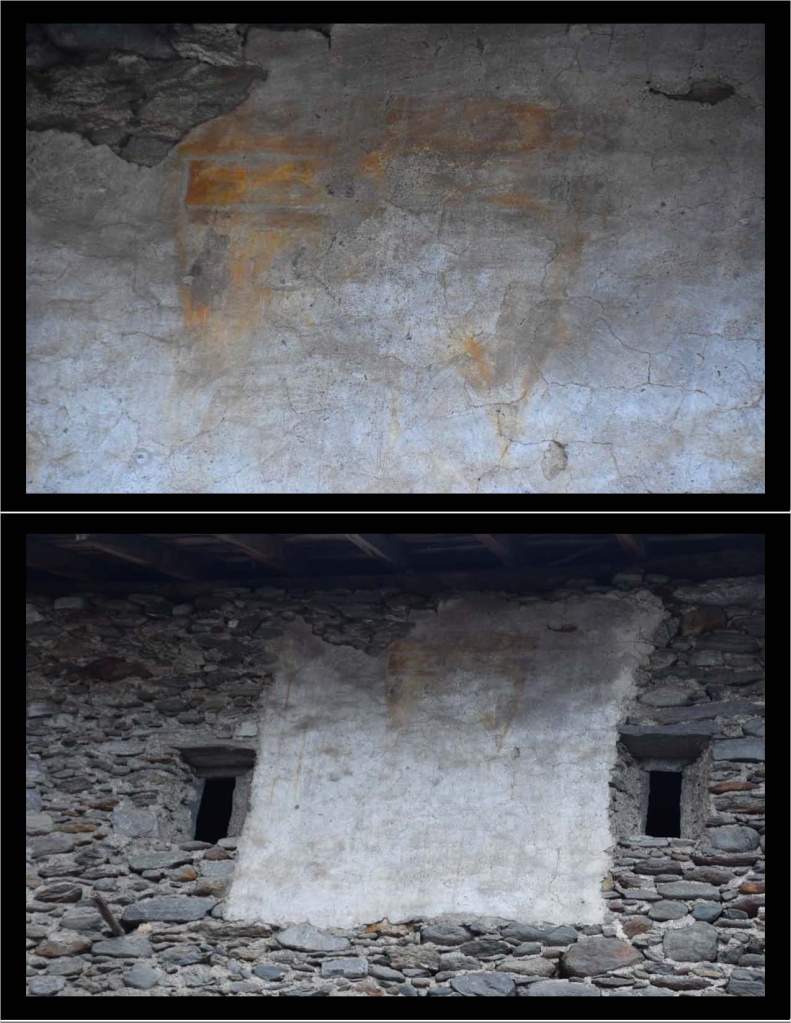

This is a series of old homes behind which runs the agro-silvo-pastorale road leading into the summer pastures on the Lesina Valley. The old homes constitute a double row between which ran a dirt road – now a grassy lane. The buildings are used as barns and – as is seen here – to store wood. Many of the homes in the Valtellina have no heating systems and even when restored families will continue to heat the kitchen/living room area with wood. Wood is ‘free’ here if one is willing to travel into the mountains to cut it.

A very colorful and quirky restored home is surrounded by unrestored homes mostly used as barns. What follows are the modern Wall Madonna’s I found in the village. This ‘modern’ home begins the walk through a historic tradition of devotion continued in our current time.

This statue of Jesus sits on a pillar in front of the rectory for the parish church. The building it decorates is in the church piazza and next to the city hall for the town. The city hall or Municipio is, very often, in the same piazza as the parish church.

This is a modern Wall Madonna that is a copied image of a famous 17th-century painting. John the Baptist is to the left and Saint Joseph is to the right. The Madonna is on a very large villa that is at the end of the eastern end of the village. The gardens are filled with flowers and greenery.

This is the best photo I could get of this shrine dedicated to Jesus. The shrine welcomes one to the lane that leads to the entry door of the villa previously described.

I finish this visual narrative with a lovingly placed modern Wall Madonna – a sacred space preserved!